A story gives about as much relief as a palm tree, which is some. A thin stretch of shade in the heat when the daylight is right. It can be enough depending on where else you have to go.

I was working on a story about a long time ago, when I drifted away and started wandering around outside of myself. With that story, I tried to track down where I went. I wrote out lots of versions of it. They all worked for a little. For a little I found myself. But the sun keeps moving further across the sky.

In the story here I am attempting not to find myself but find what I escaped from, which I think was a child, or a body, or both.

***

This story is that my parents were adults the whole time that my sister and I were children. I like this story because it asks me remember what I believe about adults and children.

Adults are deep wells of questions: Do I love? Are my needs important? Am I meant to live? Adults are also battling against the feeling that there is no time to ask their questions, let alone to receive answers. So adults often feel scared, and angry that they are scared, and confused about their anger.

Children are deep wells of instinct, of answers to these questions: Yes, I love. Yes, my needs are important. Yes, I am meant to live. Children absorb their answers in small doses, through the fluids and the voices that suspend them in the womb. And the answers that they aren’t born with, they find once they arrive here. They find them in the moonlight and in their milk. They drink them in during the early days of their lives.

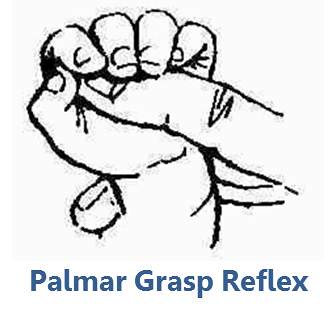

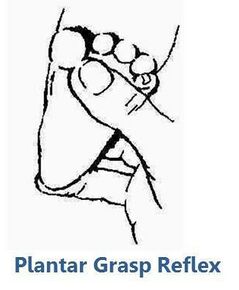

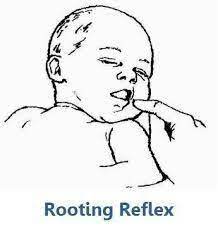

I believe this because of what I learned about newborns in Developmental Psych last year. They instinctively wrap their entire hand around a single finger and hold onto it with all the strength they have, and they reflexively begin to suck when they sense that something is near their mouths. Before we are taught to know anything else, we know to love, we know to need, we know to protect that source of life within ourselves.

Children and adults grow up together. Somewhere in the process of doing this they both become convinced that it’s the other way around. Children have no answers and adults have no questions.

Children start to doubt what they know about love and belonging. This happens incrementally, through lonely and compounding moments. Their fourth grade math teacher calls on them when they don’t know the answer their lunch looks and smells and tastes different than everyone else’s they lose the election for class president in eighth grade after running such an earnest and glittery campaign. They can’t find their mom in the grocery store. They can’t find her at home either. In these moments it feels like a dangerous mistake, to be sure of oneself.

If and when the adults see the children beginning to doubt themselves, they panic. They panic because they don’t know what to do. They can’t seem to console the doubt and they can’t seem to take away its power either. But they are so desperate for it to go away because they don’t have the room for it. They already have so much doubt of their own. They’ve been carrying it for years.

It looms above them and swirls within them and through more lonely and compounding moments, the adults have come to believe that the only way to be brave is to act as though they doubt nothing. Adults hope that if they doubt their own doubt enough it’ll all be squashed into nothing. So the last thing the adults think to do is show their doubt to the children. And so the children learn that the way they should be is not the way that they are.

And then everyone only has questions and no one remembers their answers. The adults become even angrier and more confused. They are frightened to see their own fear reflected back to them in the children, their dearest and purest mirrors. They sense that the lava of their precious answers has drained out of them, hardened in the cool air into questions. And they feel as though they are suffocating.

My sister and I were children and my parents were adults: everyone was forgetting that they were missing nothing and that they had been born with all that they needed: no one trusted that their love and belonging wasn’t threatened just buried: no one knew how to return to it.

***

When everyone is missing from themselves and when you are too, it doesn’t make sense for you to stay where you are, as you are. So it makes sense to leave. So I left.

I left behind a little body. A little body shivering in many places. The cold bathroom the cold refrigerator the cold porch. One day there is going to be another story about this.

But for now the only story I’ve got is that I left because I was searching for something else. Anything else that was not a cold little body full of questions, full of doubt. And of course I did. I didn’t know how to stay warm in such a cold body.

I had to leave anyway because the story has to end with me returning. There’s no way to return if you never go away in the first place. The same way there is no way to remember if you have not forgotten.

In the very end, returning and remembering are far more important to me than having always stayed and having always known (these are the processes of someone who is alive).